Reflections on Actionable Science for IPY-5 (2032–33)

As we look ahead to the next International Polar Year in 2032–33 (IPY-5), Øystein Hov from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, has been thinking increasingly about one of its core ambitions: the commitment to produce actionable insights. This phrase appears frequently in planning documents, but what does it really mean in practice? And how can IPY-5 ensure that our collective scientific effort leads not only to new knowledge, but to outcomes that matter for people, communities, and operations?

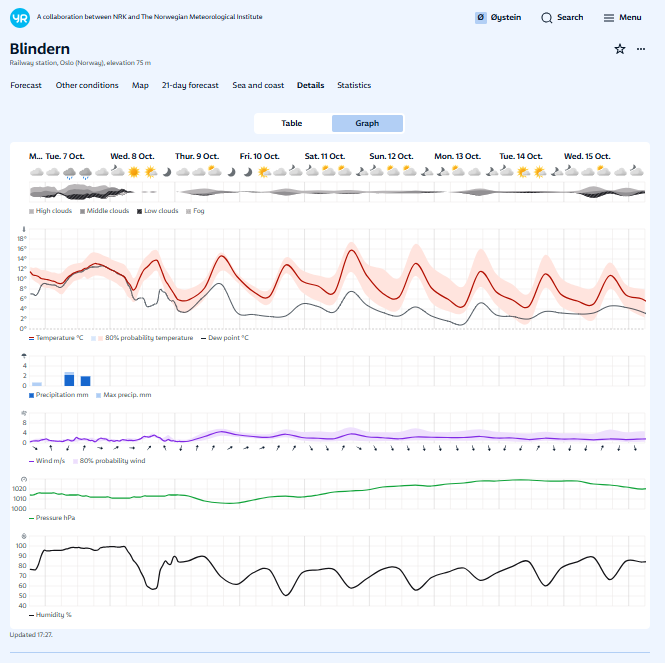

Yr is a product of actionable science.

Screenshot of Yr, via Øystein Hov.

In my view, this requires a shift in how we conceptualize the relationship between research and practice. For many years, science has been organized as a largely linear enterprise. Researchers generate results, publish them, and hope that someone — a decision-maker, a service provider, a manager — will find and use them. But experience shows that this one-way transfer often falls short. Information gets lost, arrives too late, or fails to match the context where decisions are actually made.

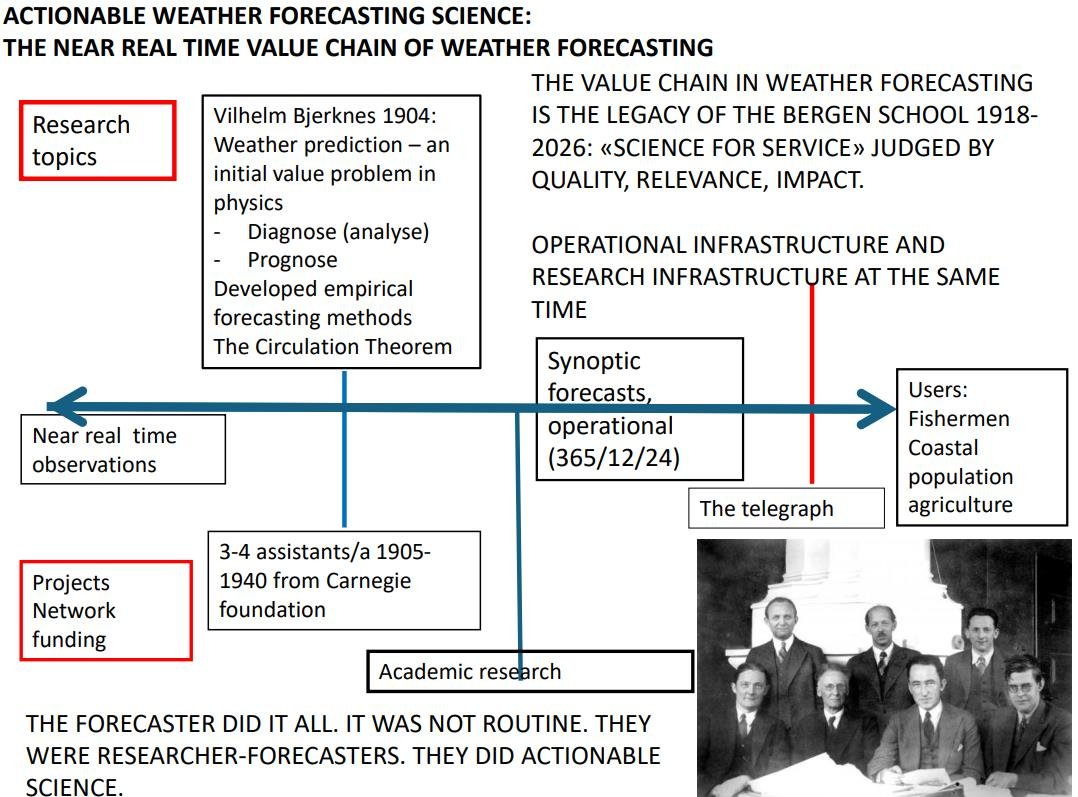

Figure from Øystein Hov’s poster at the 2025 Svalbard Science Conference.

What I advocate instead is an iterative, cyclical model in which research and operational practice develop together. In this structure, the Community of Research and the Community of Practice are not separated by institutional boundaries but linked by continuous interaction. Operational services provide insights, needs, and constraints that shape research questions, while scientific developments feed back into improved forecasting, observation, and decision-support systems. This “value cycle” is sustained by enablers such as legislation, funding instruments, data infrastructures, and long-standing institutional partnerships.

Why is this so important now? Because the Arctic and Antarctic are changing rapidly, and the challenges we face — from climate adaptation to environmental risk management and security concerns — are increasingly complex. Addressing such challenges demands knowledge that is not only accurate but also usable. Actionable science supports both the daily work of operational agencies and the long-term planning of policymakers and communities. It helps protect lands, waters, wildlife, and people.

To judge whether we succeed, we need to evaluate scientific outcomes more broadly than we traditionally have. Publications remain essential, but they cannot be the only measure. Actionable science includes assessments developed in response to societal needs, technological innovations such as models, instruments and observational capabilities, FAIR and well-curated datasets, operational services informed by Earth system predictions, effective communication, trusted scientific advice, and the education of a new generation capable of navigating the space between research and operations. Many national meteorological services have adopted such an actionable science model. Internationally, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) is a very good example.

Underlying all of this is the importance of trust. Actionable science emerges when researchers and practitioners view each other not as endpoints of a process, but as partners in joint exploration. Trusted relationships allow ideas to flow in both directions. They make it possible for research to respond to real needs and for operational services to benefit from scientific curiosity and creativity.

As we move toward IPY-5, I am hopeful that we can embrace this more integrated view of the scientific enterprise. If we do, then the insights generated during IPY-5 will not only expand our understanding of the polar regions — they will also strengthen our ability to act, adapt, and prepare for the future. That, to me, is the essence of actionable science.