Tackling harassment in polar research - lessons from polar science worldwide

The polar regions are experiencing dramatic changes, with communities and ecosystems bearing the brunt of these transformational impacts. Though polar research has contributed significantly to a better understanding of our planet's changing climate, attention must also be paid to the historical roles and structures underpinning polar research itself, as well as the importance of safety in both the field and the workplace. Not only does harassment affect individual well-being, it also disrupts the scientific mission. PCAPS aims to help facilitate inclusivity of early career researchers and minorities in the field of polar science by helping elevate the discussion on important issues, such as harassment, that need to be addressed.

Students setting up a weather station in Petuniabukta, Svalbard. Photo credit: Vera Stockmayer

An important part of conducting research in the polar regions is fieldwork, often in harsh environments and extreme weather conditions, where the work is also heavily reliant on well-functioning small, tight-knit teams. Polar research stations are remote, leaving the researchers cut off from outside support systems. Polar researchers and support personnel often live and work together for extended periods of time, creating an environment where tensions can escalate quickly.

In an isolated, confined and extreme (ICE) environment such as those found in the polar regions, trust, collaboration and mutual respect between team members is not just important, but essential. For underrepresented groups such as women and early career researchers - and particularly for those who belong to multiple marginalised groups -, the challenges of fieldwork can be enhanced by hierarchical team structures.

In a 2017 survey on women's experiences in Antarctica with the Australian national program, 63% reported having experienced inappropriate remarks when in the field, but only half of them took action as speaking up can feel impossible in ICE environments. Similar findings apply to other national contexts.

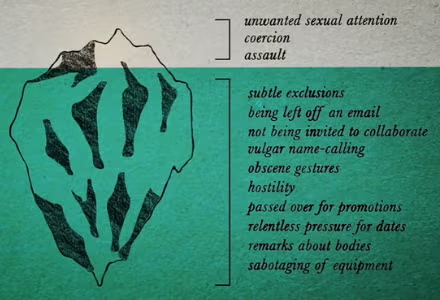

Harassment in science can be illustrated with an iceberg. The obvious, big actions are the tip of the iceberg. There are, however, countless other actions that can be more subtle that lie below the surface. Figure credit: Sharon Shattuck and Ian Cheney

Harassment amplifies feelings of isolation, stress and fear that might already be present. The mental and emotional toll of working in such conditions is intensified when researchers feel unsafe or disrespected, creating an environment where it becomes difficult to thrive. Talented researchers, especially women and minorities, can potentially be driven out of the field altogether. Systematic change can help ensure everyone feels safe and welcome in polar research. However, creating such a culture is the responsibility of us all.

In PCAPS, we are committed to fostering scientific collaboration between different disciplines and across different career stages as well as engaging underrepresented groups via our Inclusivity Objective. We work to support early career researchers and underrepresented groups to gain important career opportunities in polar research. Polar research plays a key role in improving global weather forecasts and understanding climate change. We at PCAPS believe that an interdisciplinary and diverse research environment is the way forward for improved environmental forecasting in the polar regions.

Creating a safe and inclusive environment in polar research begins with open conversations, acknowledging power imbalances, and a collective commitment to respect and support. All team members should have an awareness of intersectionality, and the ways this means one person’s experiences can differ from another’s, even in the same situation. The well-being of researchers should be prioritized as highly as the science itself because, after all, it is people who do the science. National Antarctic Programs have a responsibility to provide safe work environments. The importance of a leader taking responsibility and accountability for setting clear expectations and creating a safe and respectful work environment is not to be understated, but this starts long before any field campaign begins. Cultural change - including attitudes around, for example, who belongs in Antarctica - takes dedicated leadership and time.

Polar research is a significant piece in the puzzle to understand and respond to the challenges facing our planet. The field requires resilience, diversity and teamwork to address some of the most pressing questions of our time. But research cannot thrive in environments where harassment and exclusion persist. By explicitly addressing harassment and deliberately fostering inclusion, we can build a safe foundation for conducting the crucial research that is needed for the whole planet.

We hope to see a thriving and safe community of researchers, both early in their careers and established researchers, collaborating to find the best solutions to improve environmental forecasting in the polar regions.